Difference Between Reading on Paper and Reading on a Computer Display.

What issue exercise digital devices have on our digital brains? To uncover the influence on learning of using digital tablets for reading, the Coast Guard Leadership Evolution Heart conducted an experiment to define differences in recollect and comprehension between tablet and newspaper readers.

Every bit of 2014, 63 per centum of colleges reported using e-textbooks, while 27 per centum planned to in the near future. 1 Simply what drives these digital book policies and practices in college education — technology or research?

Considering the pervasiveness of digital devices, the lack of sufficient guidance for educators to make informed decisions about pedagogy and learning is disconcerting. Despite the widespread adoption of tablets in schools, ranging from elementary through college education, research almost the effects of tablet use on educatee learning has obvious gaps. Rapid technological advances and changing features in electronic devices create challenges for those who study the effects of using them; specifically, researchers face limitations in understanding the effects of digital reading on student recall and comprehension. More than important, increasing our agreement of the influence of electronic devices on learning volition inform educators near the implications of test scores and performance.

Digital Brains: What Research Reveals

"Nosotros're spending so much fourth dimension touching, pushing, linking, scrolling and jumping through text that when we sit down with a novel, your daily habits of jumping, clicking, linking are simply ingrained in you lot."

—Professor Andrew Dillon, University of Texas, who studies readingii

Research yields conflicting results in learning betwixt digital and paper reading in part due to advances in technology and design features.three While some contradictions reverberate variations in research blueprint and methodology, other differences may result from page layouts, such as single- or double-cavalcade format. Despite challenges from continuous technological enhancements, studies that investigate differences between digital and paper learners contribute to our understanding of cognitive processes. Collectively, results propose that students engage in different learning strategies that might short-circuit comprehension when interfacing with digital devices compared to print.

Short Circuits

Researchers accept noticed changes in reading beliefs every bit readers adopt new habits while interfacing with digital devices.4 For case, findings by Ziming Liu claimed that digital screen readers engaged in greater use of shortcuts such equally browsing for keywords and selectivity.5 Moreover, they were more probable to read a document only once and expend less time with in-depth reading. Such habits raise concern almost the implications for academic learning.

According to Naomi Baron, academy students sampled in the United States, Frg, and Nippon said that if price were the same, about 90 percent adopt hard re-create or print for schoolwork.6 For a long text, 92 percent would cull hard copy. Baron also asserts that digital reading makes information technology easier for students to become distracted and multitask. Of the American and Japanese subjects sampled by Baron, 92 percent reported they constitute it easiest to concentrate when reading in hard copy (98 percent in Federal republic of germany). Of the American students, 26 percent said they were probable to multitask while reading in print, compared with 85 percent reading on-screen.

David Daniel and William Woody urge caution in rushing to e-textbooks and phone call for further investigation.7 Their study compared college educatee performance betwixt electronic and newspaper textbooks. While the results suggested that student scores were like between the formats, they noted that reading fourth dimension was significantly higher in the electronic version. In addition, students revealed significantly higher multitasking behaviors with electronic devices in dwelling conditions. These findings uphold contempo results involving multitasking habits while using e-textbooks in Baron's survey.8 Likewise, 50. D. Rosen et al. found that during a 15-minute study menses, students switched tasks, on average, three times while using electronic devices.9 Taken together, these studies indicate to adaptive habits and cerebral shortcuts while using technology even though learning is the primary objective.

Development and Functioning

A 2013 United kingdom survey conducted by the National Literacy Trust with 34,910 students ranging in age from 8 to xvi reported that over 52 percent preferred to read on electronic devices compared to 32 percent who preferred print.ten The data points to possible influences of technology on reading power: compared to print readers, those who read digital screens are nearly twice less likely to be above-average readers. Furthermore, the number of children reading from e-books doubled in the prior ii years to 12 percent. Co-ordinate to John Douglas, the National Literacy Trust Director, those who read but on-screen are as well three times less likely to savor reading. Those who read using technological devices said they really enjoyed reading less (12 percent) compared to those who preferred books (51 percent).

Survey results from the Joan Ganz Cooney Center advise that parents who read to their 3- to six-year-olds with tablets recalled significantly fewer details compared to the same story read using print.11 Together, data from these studies raise concern about overall literacy development in young people.

"Because we literally and physiologically can read in multiple means, how we read — and what we absorb from our reading — will be influenced by both the content of our reading and the medium nosotros use." 12

—Maryanne Wolf

Natalie Phillips conducted fMRI studies to examine brain action of graduate students while reading Jane Austen (deep reading for literary analysis and reading for pleasure).13 Co-ordinate to Phillips, the inquiry squad saw dramatic increases in blood menstruation to diverse cognitive regions of the brain far beyond those responsible for executive function, regions associated with tasks requiring close attention, suggesting that how people read may be as important as what they read. Phillips concluded, "It's non simply the books we read, but also the act of thinking rigorously most them that'due south of value, exercising the brain in critical ways."14

For case, Ackerman and Goldsmith sought to empathise differences in university students' metacognition skills and the consequence on the learning procedure between digital and paper reading modes.15 Compared to digital readers, Ackerman and Goldsmith purported that paper readers manifested greater self-regulation that resulted in improve performance. Mangen, Walgermo, and Bronnick conducted an experiment investigating comprehension with high school students to make up one's mind differences between paper and digital forms.16 Students completed an open up-book test (hour-long) while they reviewed and navigated either a digital or newspaper reading. According to the researchers, newspaper readers showed significantly higher comprehension scores compared to digital readers.

Findings from Johnson's experiment illustrate the challenges in replicating effects.17 Studies by Johnson and Mangen, Walgermo, and Bronnick compared digital and paper textbook readings followed by open-book assessments. Nevertheless, Johnson'due south experiment consisted of college students, whereas Mangen and colleagues studied high schoolhouse students. Results from Johnson's study did not indicate pregnant differences in group test scores between digital and textbook readings,18 contrasting with findings by Mangen's team.19 What'south more, Johnson's findings were independent of student preferences for either newspaper or tablet.

Method: Newspaper or Tablet

Similar to other educational institutions, students at the Coast Baby-sit Leadership Development Middle use digital tablets for reading assignments (figure i). However, we lacked research information to inform us about the effects on our students' learning or performance. Therefore, to uncover the influence on learning of using digital tablets for reading, I conducted an experiment to ascertain differences in call up and comprehension between tablet and paper readers.

Photo: Dave Plouffe, U.S. Coast Guard Leadership Development Heart

Effigy i. Senior Enlisted Leadership Course students use tablets for course readings.

I randomly assigned students from existing class groups, enrolled in leadership courses (Due north = 231), to read either digital (n = 119) or paper (due north = 112) versions of a leadership article.20 The experiment consisted of two conditions: paper and tablet readers as the contained variable, and assessment scores from each grouping as the dependent variable. The randomly assigned groups read either a digital tablet or paper version of the same leadership article, approximately 800 words in unmarried-cavalcade format.21 After the reading, students completed an assessment consisting of 10 multiple-pick items for think accuracy and 2 short essay questions for comprehension.

Two hypotheses were tested:

- H1: Students who read a paper commodity will have a statistically significant difference in greater recollect accurateness as shown by exam scores compared to those who read the same digital article using a tablet.

- H2: Students who read a paper article will take a statistically significant difference in reading comprehension every bit shown by higher test scores compared to those who read the same digital article using a tablet.

Results

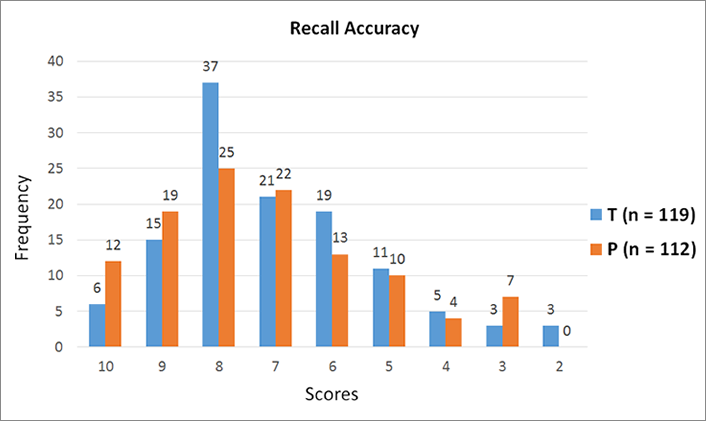

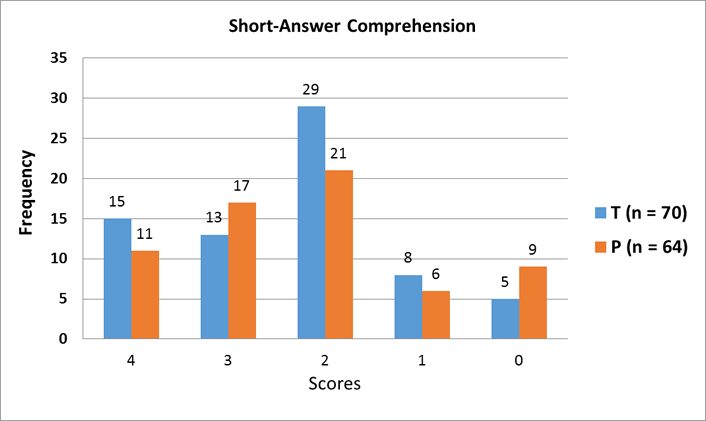

The total sample size comprised 231 students, 119 digital tablet and 112 paper readers. The x multiple-option items were scored 10–0 (high to low), while the 2 brusk-answer items were coded for comprehension (4–0, high to low). To decide grouping differences, t-tests compared scores between paper and tablet readers. Results did not show a statistically meaning deviation in group means between newspaper and tablet readers for either the multiple-choice or curt-answer items.

Yet, an examination of the range and frequencies of score distributions indicated an emerging pattern: Compared to tablet readers, paper readers had greater frequencies of college scores for both multiple-choice retrieve and brusk answers that measured comprehension (tables 1 and 2; figures 2 and 3). When combining the summit two scores for comprehension, paper readers showed a higher percentage. Although there is a greater frequency of score four with tablets, this corresponds with a college frequency and percentage of the mean score, 2. Despite no difference between grouping ways, there may be a divergence in individual scores. In detail environments or for specific test purposes such as military selection and ranking, this might signal a significant factor.

Table 1. Frequencies, multiple-option, recall (Due north = 231)

Note: High to low score (10–0).

| Score | Frequency Tablet (northward = 119) | Percentage Tablet | Frequency Newspaper (due north = 112) | Percent Newspaper |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | six | 5% | 12 | eleven% |

| 9 | xv | 13% | 19 | 17% |

| viii | 37 | 31% | 25 | 22% |

| vii | 21 | eighteen% | 22 | twenty% |

| vi | nineteen | sixteen% | 13 | 12% |

| 5 | xi | 9% | ten | 9% |

| 4 | 5 | 4% | four | four% |

| 3 | 3 | iii% | vii | 6% |

| 2 | 3 | 3% | 0 | 0% |

Tabular array 2. Short answers, comprehension (North = 134)

Note: Students for this sample were drawn from the same course. High to low score (4–0).

| Score | Frequency Tablet (n = 70) | Per centum Tablet | Frequency Paper (n = 64) | Pct Paper |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 15 | 21% | 11 | 17% |

| iii | thirteen | 19% | 17 | 27% |

| 2 | 29 | 41% | 21 | 33% |

| 1 | 8 | 11% | half-dozen | 9% |

| 0 | five | 7% | nine | 14% |

Effigy 2. Multiple-option items measuring call up accuracy, high to low score (x–0)

Figure 3. Brusk-respond comprehension scores of students drawn from same course; low to high score (0–4)

Results: Hypotheses

H1: Students who read a newspaper article will have a statistically pregnant divergence in greater retrieve accurateness equally shown by test scores compared to those who read the same digital article using a tablet was not supported.

H2: Students who read a paper commodity will have a statistically pregnant difference in reading comprehension as shown by higher exam scores compared to those who read the aforementioned digital article using a tablet was non supported.

Although there were no significant differences in group means, there were differences in score frequencies for both recall and comprehension.

Individual score differences can exist of import for ranking and selection purposes, as in war machine domains or in granting awards.

To further explore elements that influence examination scores, a second experiment replicated the start design and method while also probing for additional factors. Consequently, data collection extended to include (1) student frequency of reading on digital devices for coursework versus paper, and (2) higher educatee condition (N = 205). Comparable to the outset experiment, no group differences in hateful scores appeared between paper (n = 103) and tablet readers (n = 102), but the blueprint of greater frequencies of higher scores for newspaper readers continued. Unexpectedly, frequency of digital device apply and college status produced no significant difference.

Discussion and Implications

Johnson's finding offers an interesting comparing with those of this report. Both studies were conducted during the same yr and used the same brand of digital tablet (iPad), allowing comparisons between features of the experiments equally depicted in table 3.

Table 3. Niccoli vs. Johnson study comparison 22

| Niccoli Study (N = 231) | Johnson Written report (N = 233) |

|---|---|

| iPad tablet vs. paper | iPad tablet vs. paper |

| Unfamiliar reading | Unfamiliar reading |

| Two-page article | E-textbook chapter |

| Closed-book examination | Open-book test |

A comparative evaluation of the results from both studies indicates two similar patterns:

- No significant difference in group test score ways between digital tablet and newspaper readers

- Higher frequency rates for paper readers of the two highest scores (for recall and comprehension)

Note that both studies display similar patterns in score distributions despite differences in reading length (two pages vs. a affiliate). What's more, the patterns were comparable even though this study was a closed-book assessment compared to Johnson's open book. However, the shorter reading length for this study and the open-book feature of Johnson's may nowadays pattern limitations that influenced results.

Furthermore, both experiments showed no departure in grouping means, even though the samples differed demographically. Whereas Johnson's study consisted of traditional college students, those for this written report were military students with approximately eight years of professional person experience.23

Maybe a longer reading combined with a closed-volume cess will reveal pregnant differences, peculiarly in comprehension scores. Individual differences of higher scores of paper readers from this study and Johnson's may reflect factors related to working retention. Studies of reading from computers conducted by Wastlund, Norlander, and Archer highlighted the influence of page layout and scrolling on cerebral need and individual working retentiveness capacity.24 Likewise, experimental results by Noyes and Garland suggested that reading from screens might interfere with cognitive processing of long-term retentivity.25

Inconsistencies in cognitive load, reading complexity, written report notes, and environment (i.e., classroom, home, and workplace) present contributing factors that influence performance results. Baron asserted that 92 pct of students find it easier to concentrate while reading from paper compared to electronic texts.26 According to Mangen, Walgermo, and Bronnick's study, students who used hard-copy texts performed meliorate in comprehension scores compared to those with computers for an open-book assessment.27 Moreover, as reported past Muller and Oppenheimer, students showed college recall and conceptual scores when studying handwritten notes compared to electronic notation taking.28 All together, several design qualities point to variables that contribute to contradictory results.

Final Thoughts and Recommendations

Uncertainties remain well-nigh the influence of digital reading for in-depth reading comprehension for adults and enhance more unanswered questions nearly the developmental implications for children.29 The furnishings of reading from digital devices on children's cognitive developmental skills and literacy abilities are just offset to emerge. Questions linger regarding the consequences of nonlinear reading on brain processing, especially adaptive shortcuts due to scrolling, scanning, and hyperlinks.30"At that place is physicality in reading," explained developmental psychologist and cerebral scientist Maryanne Wolf of Tufts University, "peradventure even more than we desire to remember nigh as nosotros lurch into digital reading — as nosotros move forwards perhaps with too little reflection. I would like to preserve the absolute best of older forms, only know when to utilise the new."31

Although current findings are conflicting and inclusive, future studies may shed light on the number of variables involved with digitized text and identify features that impede cerebral processing.

If educators understand the furnishings of digital reading on the development of deep reading and students' grasp of hard material, they can formulate instructional decisions. Given the current pace of technological change, educators should seize opportunities to further accelerate our understanding of students' learning while using electronic devices.

Recommendations

- Consider assigning longer readings that create a slight increase in cerebral load for digital readers.

- Include a longer time interval betwixt assigned reading and assessment of students' recall and comprehension.

- Extend these studies of digital vs. newspaper reading to main and secondary students to explore their effects on learning and on children's developmental patterns.

- Consider other factors that might impact recall and comprehension among readers using digital and paper texts, such as the types of reading (deep, belittling reading vs. pleasure reading, for example) and the academic field of study of the students studied.

Acknowledgments

The enquiry in this commodity was presented in the Digital Devices, Digital Brains session at the NERCOMP 2015 Briefing.

Sincere appreciation to the volunteer participants of Boat Forces School, Main Warrant Officers Professional Evolution School, Officeholder Candidate School, and Senior Enlisted Leadership Course students at the U. S. Coast Baby-sit Leadership Development Eye. Special thanks to the school chiefs for their support in granting time for this study.

Notes

- "Learning technologies being used or considered at colleges, 2013," Annual of Higher Educational activity, Chronicle of College Pedagogy, August 18, 2014.

- Michael S. Rosenwald, "Serious reading takes a hit from online scanning and skimming, researchers say," Washington Mail, April 6, 2014.

- See, for example, Jim Johnson, "Students perform well regardless of reading print or digital books," ScienceDaily, May 24, 2013; Anne Mangen, Bente R. Walgermo, and Kolbjorn Bronnick, "Reading linear texts on paper versus computer screen: Effects on reading comprehension," International Journal of Educational Research, Vol. 58 (2013): 61–68, DOI: 10.1016/j.ijer.2012.12.002; and Erik Wastlund, Torsten Norlander, and Trevor Archer, "The event of page layout on mental workload: A dual-chore experiment," Computers in Homo Behavior, Vol. 24, No. 3 (May 2008): 1229–1245, DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2007.05.001.

- Maryanne Wolf, "Our 'Deep Reading' Brain: Its Digital Development Poses Questions," Nieman Reports (Summertime 2010), Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University.

- Ziming Liu, "Reading behavior in the digital environment: Changes in reading behavior over the past x years," Journal of Documentation, Vol. 61, No. vi (2005): 700–712.

- Naomi Due south. Businesswoman, "How E-Reading Threatens Learning in the Humanities," Chronicle of Higher Education, February 24, 2015.

- David B. Daniel and William Douglas Woody, "E textbooks at what cost? Functioning and utilise of electronic vs. impress texts," Computers in Education, Vol. 62 (March 2013): xviii-23, DOI: 10.1016/j.compedu.2012.x.016.

- Baron, "How Due east-Reading Threatens Learning in the Humanities."

- L. D. Rosen, K. Whaling, L. M. Carrier, Northward. A. Cheever, and J. Rokkum, "The Media and Engineering science Usage and Attitudes Scale: An empirical investigation,"Computers in Human being Behavior, Vol. 29, No. six (2013): 2501–2511.

- National Literacy Trust, "Children'due south on-screen reading overtakes reading in print," Media Heart, May 16, 2013 [http://www.literacytrust.org.britain/media/5371].

- Sarah Vaala and Lori Takeuchi, "QuickReport: Parent Co-Reading Survey," Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop, September thirteen, 2012.

- Wolf, "Our 'Deep Reading' Encephalon."

- Natalie Phillips, interviewed in "MSU lab examines literature's furnishings on the encephalon," Current Country podcast, WKAR, October 22, 2013.

- Tom Oswald, "Reading the classics: Information technology is more than simply for fun," MSU Today, September 14, 2012, Michigan State Academy.

- Rakefet Ackerman and Morris Goldsmith, "Metacognitive regulation of text learning: On screen versus paper," Journal of Experimental Psychology: Practical, Vol. 17, No. 1 (March 2011): eighteen–32, DOI: 10.1037/a0022086.

- Mangen, Walgermo, and Bronnick, "Reading linear texts on paper versus computer screen."

- Johnson, "Students perform well regardless of reading print or digital books."

- Mangen, Walgermo, and Bronnick, "Reading linear texts on paper versus computer screen."

- Johnson, "Students perform well regardless of reading print or digital books."

- Anne Grand. Niccoli, "The Effects of Reading Way on Recall and Comprehension," Paper 2, NERA Conference Proceedings 2014 (2015).

- Amaani Lyle, "Chairman Champions Character in Graduation Address," DOD News, June xiii, 2013, American Forces Printing Service, U.S. Department of Defence force.

- Niccoli, "The Effects of Reading Mode on Think and Comprehension"; and Johnson, "Students perform well regardless of reading impress or digital books."

- Ibid.

- Wastlund, Norlander, and Archer, "The issue of page layout on mental workload."

- Jan Noyes and Kate Garland, "Computer- vs. paper-based tasks: Are they equivalent?" Ergonomics, Vol. 51, No. 9 (September 2008): 1352–1375.

- Baron, "How E-Reading Threatens Learning in the Humanities."

- Mangen, Walgermo, and Bronnick, "Reading linear texts on newspaper versus computer screen."

- Pam Mueller and Daniel Oppenheimer (2014, Jun iv). "The pen is mightier than the keyboard: Advantages of longhand over laptop notation taking," Psychological Science, Vol. 25 (June 4, 2014): 1159–1168; Rosenwald, "Serious reading takes a hitting from online scanning and skimming"; and Maryanne Wolf and Mirit Barzillai, "The Importance of Deep Reading" [https://www.mbaea.org/media/documents/Educational_Leadership_Article_The__D87FE2BC4E7AD.pdf] Educational Leadership, Vol. 66, No. 6 (March 2009): 32–37.

- Wolf and Barzillai, "The Importance of Deep Reading."

- Rosenwald, "Serious reading takes a hit from online scanning and skimming"; Wolf, "Our 'Deep Reading' Brain."

- Maryanne Wolf, quoted by Ferris Jabr, "The Reading Encephalon in the Digital Historic period: The Science of Paper versus Screens," Scientific American, April xi, 2013.

Anne Niccoli, EdD, is an instructional systems designer, Functioning Support Department, U.S. Coast Baby-sit Leadership Development Eye. She develops curriculum and training programs that cultivate leadership skills for U. Southward. Coast Guard officer and enlisted personnel. Dr. Niccoli strives to design and instruct resident and composite learning courses to foster critical thinking. In addition to creating the Leadership Development Resource portal, she was a member of the Unit of measurement Leadership Evolution Implementation team awarded the Coast Guard Meritorious Team Commendation. Niccoli holds a doctorate in Instruction and qualifications in Instructional Systems Blueprint, Chief Grooming Specialist, and Coast Guard Instructor.

Source: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2015/9/paper-or-tablet-reading-recall-and-comprehension

Postar um comentário for "Difference Between Reading on Paper and Reading on a Computer Display."